All Article Properties:

{

"objectType": "Article",

"id": "2957203",

"signature": "Article:2957203",

"url": "https://prod.dailymaverick.co.za/opinionista/2025-11-02-moral-panic-or-measured-response-the-politics-behind-sas-elephant-crisis/",

"shorturl": "https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/opinionista/2957203",

"slug": "moral-panic-or-measured-response-the-politics-behind-sas-elephant-crisis",

"contentType": {

"id": "3",

"name": "Opinionistas",

"slug": "opinionista",

"editor": "default"

},

"views": 0,

"comments": 1,

"preview_limit": null,

"rating": 0,

"excludedFromGoogleSearchEngine": 0,

"status": "publish",

"title": "Moral panic or measured response? The politics behind South Africa’s elephant ‘crisis’",

"firstPublished": "2025-11-02 18:10:37",

"lastUpdate": "2025-11-03 10:55:33",

"categories": [

{

"id": "435053",

"name": "Opinionistas",

"signature": "Category:435053",

"slug": "opinionistas",

"typeId": {

"typeId": "1",

"name": "Daily Maverick",

"slug": "",

"includeInIssue": "0",

"shortened_domain": "",

"stylesheetClass": "",

"domain": "prod.dailymaverick.co.za",

"articleUrlPrefix": "",

"access_groups": "[]",

"locale": "",

"preview_limit": null

},

"parentId": null,

"parent": [],

"image": "",

"cover": "",

"logo": "",

"paid": "0",

"objectType": "Category",

"url": "https://prod.dailymaverick.co.za/category/opinionistas/",

"cssCode": "",

"template": "default",

"tagline": "",

"link_param": null,

"description": "",

"metaDescription": "",

"order": "0",

"pageId": null,

"articlesCount": null,

"allowComments": "0",

"accessType": "freecount",

"status": "1",

"children": [],

"cached": true

}

],

"access_groups": [],

"access_control": false,

"counted_in_paywall": true,

"content_length": 7689,

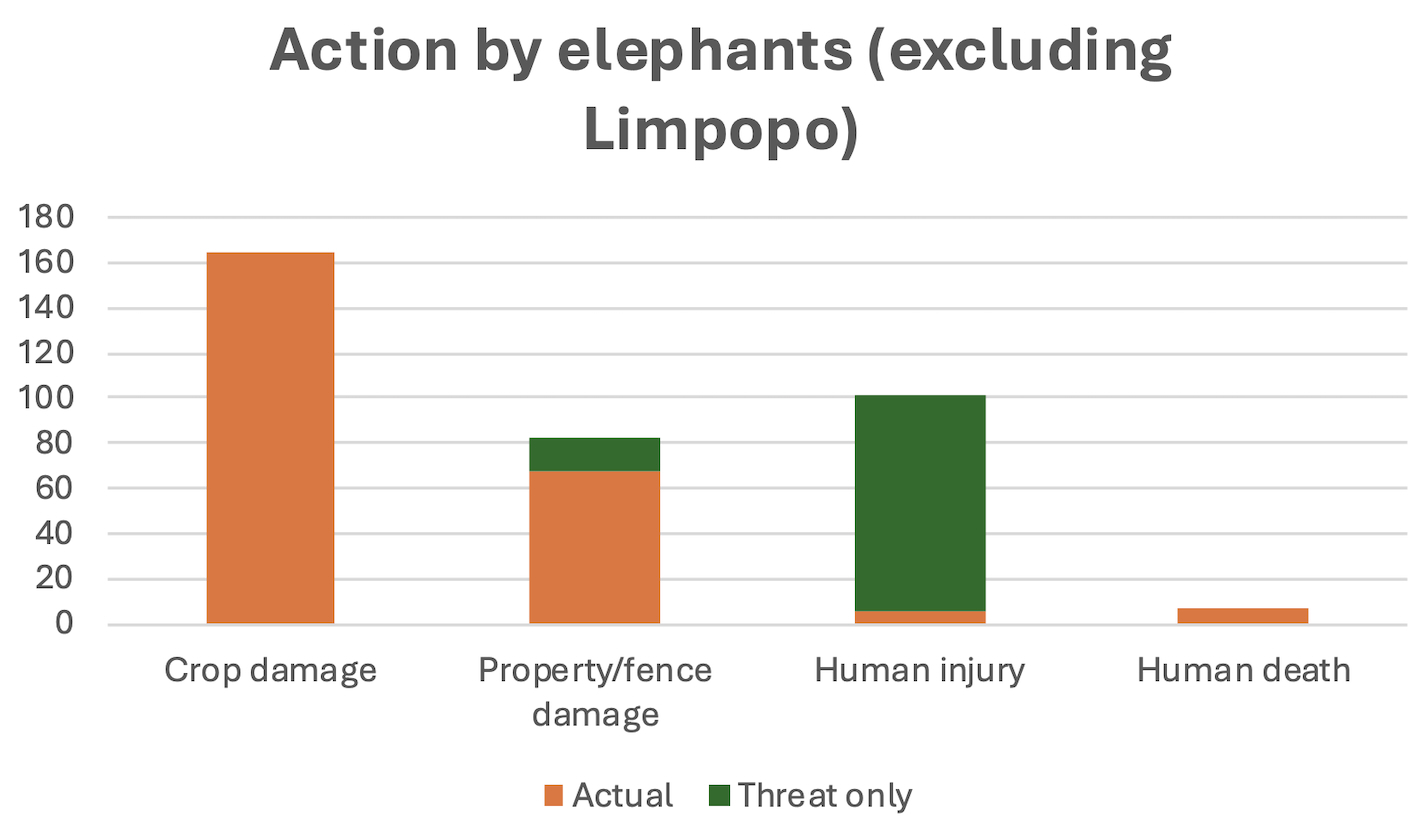

"contents": "<figure class=\"lead-media\"><a href=\"https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/labels-5/\"><img loading=\"lazy\" class=\"alignnone size-full wp-image-2890220\" src=\"https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/label-Opinion-scaled.jpg\" alt=\"\" width=\"2560\" height=\"249\" /></a></figure>\r\n<span style=\"font-weight: 400;\">Are elephants becoming increasingly dangerous to humans? Deputy Minister of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment Narend Singh seems to think so. He recently got together a million-rand conference – the Southern African Elephant Indaba – at which human-elephant conflict (HEC) was the core theme. This came as a surprise to conservation NGOs working with elephants. Even those that attended came away puzzled. Was there really a crisis?</span>\r\n\r\n<span style=\"font-weight: 400;\">It’s a tragedy for family and friends when someone is killed by an elephant. It’s also a tragedy for the elephant, which is more than likely shot. South Africa has large areas where wild animals overlap with humans and these sorts of incidents are inevitable. </span>\r\n\r\n<span style=\"font-weight: 400;\">But do “elephant attacks” constitute a national crisis? Was the minister responding to statistics he alone had seen?</span>\r\n\r\n<span style=\"font-weight: 400;\">There are many reasons for death in this country (in the past five years 442 people died on bicycles), but being mashed by a giant wild animal or ripped to pieces by a predator conjures up a particular horror. It’s also a useful call to action if you’re administering a UN </span><a href=\"https://www.unep.org/gef/index.php/projects/reducing-human-wildlife-conflict-through-evidence-based-and-integrated-approach-southern\"><span style=\"font-weight: 400;\">Global Environment Fund</span></a><span style=\"font-weight: 400;\"> totalling R460-million and titled Reducing Human Wildlife Conflict through an Evidence-based and Integrated Approach in Southern Africa. Dealing with elephant “attacks” fits that category very well. But, of course, it’s necessary to justify the spend.</span>\r\n\r\n<span style=\"font-weight: 400;\">The indaba in August involved 20 government officials, NGOs and 130 government members and </span><a href=\"https://www.conservationaction.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Q1090-Elephant-Indaba-HEC-DFFE-2-Sept.pdf\"><span style=\"font-weight: 400;\">cost just under R1-million</span></a><span style=\"font-weight: 400;\">. In answer to a parliamentary question the following month, Environment Minister Deon George justified the event, claiming that human-elephant conflict in the country had “escalated into a multifaceted conservation and socioeconomic challenge”. This included crop, infrastructure and property damage and loss of human life. </span>\r\n\r\n<span style=\"font-weight: 400;\">No technical working groups were established at or after the indaba but a list of key resolutions was issued, which embraced “sustainable utilisation” and hunting. </span>\r\n\r\n<span style=\"font-weight: 400;\">But the idea that serious elephant conflict exists had a ripple effect and has created a “moral panic” – a political science term for what happens when you lump together issues and keep flogging them until a crisis is assumed. The idea of an elephant </span><a href=\"https://the-eis.com/elibrary/sites/default/files/downloads/literature/SA_2025_08_Elephants%20and%20humans%20at%20risk_deaths_disinformation%20and%20a%20search%20for%C2%A0solutions_Daily%20Maverick.pdf\"><span style=\"font-weight: 400;\">crisis</span></a><span style=\"font-weight: 400;\"> is everywhere in the wildlife communities, with hunters </span><a href=\"https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2025-09-15-killing-without-proof-the-hidden-motives-behind-madikwes-elephant-cull-plans/\"><span style=\"font-weight: 400;\">clamouring</span></a><span style=\"font-weight: 400;\"> to solve the problem.</span>\r\n\r\n<span style=\"font-weight: 400;\">But are elephants a threat? Combining the limited available official statistics from 2021 and August 2025 plus newspaper reports, we found that in the past five years seven people have been killed by elephants. Two were elephant handlers, one a field guide, another was the owner of a game reserve and another was a suspected poacher in the Kruger Park. </span>\r\n\r\n<span style=\"font-weight: 400;\">An elderly man was killed defending his grandchildren from an elephant which they had approached on foot after alighting from their vehicle. The other two were also people who put themselves in danger – a tourist who got out of his car to photograph a breeding herd, another who left camp at night and was walking in the bush. </span>\r\n\r\n<span style=\"font-weight: 400;\">Following the indaba and in reply to another question, the minister issued a set of statistics justifying his claim. They were deeply flawed in that Limpopo, the area where many “attacks” are likely to take place (and the area where there’s the greatest clamour to hunt or cull elephants) simply failed to respond to the request.</span>\r\n\r\n<span style=\"font-weight: 400;\">However, analysis of these limited statistics shows that there were 348 elephant “incidents” over the five years, 237 actual incidents of damage or injury and 111 incidents of threats only. Of these, 165 involved crop damage and 67 were fence/property damage. </span>\r\n\r\n<span style=\"font-weight: 400;\">There were 96 separate incidents where threat of human injury was involved, four people were listed as killed (newspaper reports brought that to seven) and 86 elephants were killed. These answers come from Parliamentary Question 1,091 of 5 October 2025. Remarkably only one person was reported as being injured.</span>\r\n\r\n<img loading=\"lazy\" class=\"alignnone size-full wp-image-2957211\" src=\"https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/human-elephant-conflict-graph.jpg\" alt=\"human-elephant conflict\" width=\"1417\" height=\"829\" />\r\n\r\n<span style=\"font-weight: 400;\">A simple analysis of the average number of incidents by month or per annum does not show any indication of escalating HEC over the period. </span>\r\n\r\n<span style=\"font-weight: 400;\">Glaringly the minister disclosed that there had been no formal evaluation of the statistics of HEC incidents he had provided – a surprising answer considering the attention being focused on elephant threats and the purported escalation.</span>\r\n\r\n<span style=\"font-weight: 400;\">The statistics are nevertheless revealing: most cases of fence breaking and human contact involved incidents at often porous park boundaries where elephants raid maize, sugarcane or citrus in the growing season and water in the dry season. In many cases, elephants are described as non-aggressive unless cornered, showing avoidance more than confrontation.</span>\r\n\r\n<span style=\"font-weight: 400;\">Human deaths almost always result from defensive or surprise encounters, not proactive aggression.</span>\r\n\r\n<span style=\"font-weight: 400;\">Many entries record elephants being “shot under control operations” or “euthanised” following incursions or perceived threats, not immediate aggression. This strongly suggests a management bias towards lethal control over coexistence-based approaches.</span>\r\n\r\n<span style=\"font-weight: 400;\">Another parliamentary question (1,264 of 10 October) elicited the response that: “There are no mandatory or recommended mitigation measures that are specifically required by national legislation to be implemented before an elephant that has become a damage-causing animal may be destroyed.”</span>\r\n\r\n<span style=\"font-weight: 400;\">Elephants, when the statistics are carefully analysed, appear to be acting predictably and resourcefully, exploiting weak infrastructure and repeating learned routes. </span>\r\n\r\n<span style=\"font-weight: 400;\">This aligns with ecological displacement – elephants adapting to fragmented landscapes under increasing human encroachment or simply poor park management.</span>\r\n\r\n<span style=\"font-weight: 400;\">In most of the rest of Africa, communities live continuously with elephants. In South Africa, most, if not all, elephants are within fenced reserves. If there are incidents, it’s because these reserves – actually mainly provincial parks – are not maintaining their fences. So elephant contact with humans – apart from the very few incidents with elephant handlers and brainless tourists – is entirely the result of </span><a href=\"https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2023-05-02-more-money-better-leadership-trained-staff-how-to-prevent-sas-provincial-wildlife-gems-from-sliding-into-ruin/\"><span style=\"font-weight: 400;\">poor park management</span></a><span style=\"font-weight: 400;\">.</span>\r\n\r\n<span style=\"font-weight: 400;\">A few other questions arise: </span>\r\n<ul>\r\n \t<li>Why were 18 elephants shot <em>after</em> being returned to the Kruger Park?;</li>\r\n \t<li>Why are so many elephants being killed by trains, particularly near Luphisi, Makoko and Hazyview?;</li>\r\n \t<li>Why are elephants escaping badly fenced parks shot as problem-causing animals rather than being herded back inside?; and</li>\r\n \t<li>Why are the greatest number of incidents being recorded near Malelane Gate alongside Kruger Park?</li>\r\n</ul>\r\n<span style=\"font-weight: 400;\">But here’s the really big question: while Deputy Minister Singh outlines very real problems regarding the management and care of elephants and the communities they react with, can he justify the huge injection of United Nations money in terms of the suggested human-elephant crisis? Does he even have the evidence to prove what the grant requires an “evidence-based and integrated approach”?</span>\r\n\r\n<span style=\"font-weight: 400;\">In answer to another parliamentary question, George said the deputy minister’s statements about the escalation of incidents of HEC were based on “communication received from various organisations and communities” which “supported the notion that human-elephant conflict incidences were increasing”.</span>\r\n\r\n<span style=\"font-weight: 400;\">This is an extremely shaky basis on which to launch a moral panic about human conflict with elephants and spend millions of dollars in UN funding to solve. Which leaves a final question: is South Africa being funded because we have severe elephant-human conflict, or is elephant-human conflict advanced as a reason to accept R460-million in funds?</span>\r\n\r\n<span style=\"font-weight: 400;\">Either way, it’s very bad news for elephants. </span><b>DM</b>\r\n\r\nhttps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=REeWvTRUpMk",

"authors": [

{

"id": "339",

"name": "Don Pinnock",

"image": "https://cdn.dailymaverick.co.za/dailymaverick/wp-content/uploads/DonPortrait2.jpg",

"url": "https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/author/donpinnock/",

"editorialName": "donpinnock",

"department": "",

"name_latin": ""

}

],

"keywords": [

{

"type": "Keyword",

"data": {

"keywordId": "46254",

"name": "hunting",

"url": "https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article_tag//",

"slug": "hunting",

"description": "",

"articlesCount": 0,

"replacedWith": null,

"display_name": "hunting",

"translations": null,

"collection_id": null,

"image": ""

}

},

{

"type": "Keyword",

"data": {

"keywordId": "85390",

"name": "Don Pinnock",

"url": "https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article_tag//",

"slug": "don-pinnock",

"description": "",

"articlesCount": 0,

"replacedWith": null,

"display_name": "Don Pinnock",

"translations": null,

"collection_id": null,

"image": ""

}

},

{

"type": "Keyword",

"data": {

"keywordId": "168692",

"name": "Sustainable utilisation",

"url": "https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article_tag//",

"slug": "sustainable-utilisation",

"description": "",

"articlesCount": 0,

"replacedWith": null,

"display_name": "Sustainable utilisation",

"translations": null,

"collection_id": null,

"image": ""

}

},

{

"type": "Keyword",

"data": {

"keywordId": "202517",

"name": "elephant",

"url": "https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article_tag//",

"slug": "elephant",

"description": "",

"articlesCount": 0,

"replacedWith": null,

"display_name": "elephant",

"translations": null,

"collection_id": null,

"image": ""

}

},

{

"type": "Keyword",

"data": {

"keywordId": "413900",

"name": "opinionistas",

"url": "https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article_tag//",

"slug": "opinionistas",

"description": "",

"articlesCount": 0,

"replacedWith": null,

"display_name": "opinionistas",

"translations": null,

"collection_id": null,

"image": ""

}

},

{

"type": "Keyword",

"data": {

"keywordId": "437998",

"name": "human-elephant conflict",

"url": "https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article_tag//",

"slug": "humanelephant-conflict",

"description": "",

"articlesCount": 0,

"replacedWith": null,

"display_name": "human-elephant conflict",

"translations": null,

"collection_id": null,

"image": ""

}

},

{

"type": "Keyword",

"data": {

"keywordId": "440375",

"name": "South African elephants",

"url": "https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article_tag//",

"slug": "south-african-elephants",

"description": "",

"articlesCount": 0,

"replacedWith": null,

"display_name": "South African elephants",

"translations": null,

"collection_id": null,

"image": ""

}

}

],

"inline_attachments": [

{

"id": "2957211",

"name": "Screenshot",

"description": "",

"url": "https://cdn.dailymaverick.co.za/dailymaverick/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/human-elephant-conflict-graph.jpg",

"type": "inline_image"

}

],

"related": [],

"summary": "Behind claims of escalating human-elephant conflict lies a tangle of weak data, mismanagement and a R460-million fund that seems to need a crisis more than it proves one.",

"elements": [],

"seo": {

"search_title": "Moral panic or measured response? The politics behind SA’s elephant ‘crisis’",

"search_description": "Behind claims of escalating human-elephant conflict lies a tangle of weak data, mismanagement and a R460-million fund that seems to need a crisis more than it proves one.",

"social_title": "Moral panic or measured response? The politics behind South Africa’s elephant ‘crisis’",

"social_description": "Behind claims of escalating human-elephant conflict lies a tangle of weak data, mismanagement and a R460-million fund that seems to need a crisis more than it proves one.",

"social_image": ""

},

"time_to_read": 263,

"cached": true

}